Your cart is currently empty!

Learning Times Tables, Post

Learning Times Tables

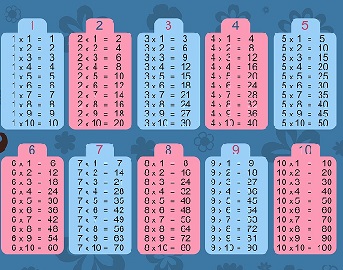

Learning Times Tables discusses Professor Jo Boaler’s paper titled “Fluency Without Fear”. The author discusses problems seen in maths education. The article focuses on memorizing the times tables.

Professor Jo Boaler, Mathematics Education Faculty, at Stanford University, wrote an article in early 2015 for https://www.youcubed.org/evidence/fluency-without-fear/

She claims children as young as 5 are suffering maths anxiety and crying on their way to school. She questions the use of the word ‘fluency’ – used in curriculum documents – in reference to recall of number facts. While conceding that some memorization of number facts is necessary, she uses the phrase ‘blind memorization’ at least twice. The view asserted in this post is:

Fluency doesn’t mean do it as fast as possible.

It means to read or do maths in an unhindered, smooth manner.

Prof Boaler is particularly opposed to timed tests on times tables. Do elementary schools in the USA do weekly tests for tables? Unless we know what is being taught, it is hard for us in other countries to judge whether there is too much. Perhaps some blame can be sheeted home to over-protective, helicopter moms? Who knows without some facts!

She makes no distinction between elementary (primary) school and high school. What students supposedly do in literacy lessons, it is presumed, is that discussing poetry and interpreting a novel are different from recalling an equation in the times tables.

By the time children get to high school, maths teachers rightly assume that students know their times tables and can do a quick recall. This, then, becomes a tool for the reasoning, problem-solving and higher order thinking required in maths – and required in other subjects.

Prof Boaler argues that English teachers do not expect students to learn ‘hundreds of words’.

>>English teachers definitely give kids “hundreds of words” to learn, but over a period of time, in ten to twenty words a week, in elementary (primary) school.

>>Not only that, students must remember numerous spelling, punctuation and language conventions, and apply them.

>>They are marked continually on them, according to their level.

>>This knowledge develops over time

Some Links: Early Primary School, Page , Middle Primary School, Page, Upper Primary School, Page, “Brick Biz” Science, Grade 5-7

The same applies to learning the times tables. The understanding comes before or after committing to memory. Memorization, application and understanding develop in tandem, usually.

Prof Boaler talks about number sense.

Take it that she means understanding of how the numeric code works.

Not to be confused with common sense or good sense, it seems.

“…Many people will argue that math is different from other subjects and it just has to be that way – that math is all about getting correct answers, not interpretation or meaning. This is another misconception.” Who are these ‘many people’? Certainly not maths teachers. If a child in primary school does get the answer correct, it might mean that the child does understand the maths problem and can solve it. Students are required to provide their working out. Teachers can allocate marks even if the answer is wrong. Been like that for a long time.

“…There is a common and damaging misconception in mathematics – the idea that strong math students are fast math students.” Is the fast student still getting the answers correct? If so, move along and give more demanding problems. The same misconception exists for Literacy — fast readers are good readers — but in the students’ minds only, and they will grow past it.

Learning times tables, for example, are

“…giving students the impression that math facts are the essence of mathematics, and, even worse that the fast recall of math facts is what it means to be a strong mathematics student…” but this passes as the child matures.

Prof Boaler suggests that even in high school, students think maths is all about recalling facts. Then the student has not progressed in understanding. That is mainly the teachers’ responsibility. That mindset will be removed with appropriate teaching and the students’ growing maturity.

The parallel in literacy education is this: Some students in elementary (primary) schools believe they have to recognise every individual word as a whole. Such struggling students need careful training to read across; read to the end of the word; read and mentally break up the components of a word.

Perhaps there is more in common with teaching Literacy and Maths than is usually believed. Prof Boaler’s presentation of learning times tables in classrooms seems somewhat muddled. Perhaps she wrote in a hurry. Nevertheless, there are some valid points and good suggestions made.